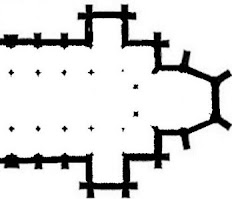

Summary. A large, basilica-shaped foundation to the second cathedral was found under the choir area, 1854. It is unlike any east end of known English cathedrals, though it has some resemblance to early Continental churches.

|

| Hamlet’s 1854 drawing of the foundation together with the published drawing by Willis, 1861. [2] |

|

| A comparison of apse sizes of early churches. |

A

comparison of apse sizes of early churches.

Large size and basilical shape do not intrinsically

indicate a specific time of construction, unless it was an Early Medieval

Romanesque church. Willis published the discovery without giving a precise date

for the foundation. It was believed Anglo-Saxons[3] did not build large in

stone, so he defaulted to thinking it was Norman. This lax thinking has

persisted and surprisingly is still claimed the second cathedral was Norman,

although there is no supporting written evidence or any other Norman stonework

existing. Several reasons for it being Early Medieval and not Norman are given

in the post, ‘The second cathedral has to be Early Medieval.’

A review of other Norman and Anglo-Norman cathedrals that

have had at some time a round apse emphasises the incomparable shape of this

foundation. The following diagrams are not to scale and dates are

approximations, but show large cathedrals, abbeys and churches which have had a

distinct, round apse.

Conjectured east end of Canterbury 1030.

The apse has a north and south porticus. It was only 9.2 m across at the chord.

The whole of the east end was changed in 1095 by extension with towers and a

chapel.

Ely 1083, but whether it had an apse is

uncertain, it was soon squared off.

Peterborough 1118.The hemispherical apse was

built on polygonal columns, later retained and enclosed in a squared end, 1500.

Norwich 1090 with site of rectangular Lady Chapel added on.

Old Sarum, Salisbury, late 12th-century.

Westminster Abbey 1245–69. A Lady Chapel

was added to give 5 apsidal chapels.

Bury St Edmunds Abbey 12th-century.

Wells 1175, squared in the 14th-century with a

polygonal chapel.

Norman cathedrals only having square-ended chancels

are St Albans, Chichester, Hereford[4], Lincoln (?), Old St

Pauls, Rochester, Southwell, Winchester (?) and York. Durham had an apse for

Cuthbert’s shrine, but then the east end was squared off; the line of the apse

can be seen in the pavement. Exeter had a five-sided apse c. 1133, but

by 1292–1308, the current squared east end was built containing several side

chapels.

It is clear Canterbury, late-10th or

early 11th-century, comes closest to being like Lichfield, if its floor plan is

true, but the overview is Lichfield apse has no obvious equivalent.

East end of St Pierre, Jumiège Abbey, showing

reconstructed floor plan for 1037–67. Soon after, c. 1040, it had a series of

small apsidioles.

Bernay Abbey 1010–55, the oldest surviving Norman

Romanesque church with a simple round apse. It might be how the east ends were

truly built in early Norman times.

A search of all Romanesque churches, 800–1200, as described

by Krautheimer[6]

and Conant[7] has failed to find a close

affinity with the apse at Lichfield with the early build of Jumièges Abbey

coming closest. There is a resemblance to St Denis Abbey, located in a suburb

of northern Paris[8].

Abbot Fulrad built a basilica church, dedicated c.775, with many

features modelled on St Peters in Rome. Partial excavation in 1938 by Crosby[9] revealed a wooden roofed

columnar basilica with a spacious adjunct extending a little beyond the aisle

walls, a lantern tower, a new kind of west end, and a simple, short, apse

extending from the east end.

Reconstructed

Basilica of Saint-Denis, the earliest Carolingian Romanesque church. Nave and

apse were 30 feet wide. The alignment of the crypt is unexplained and shape

conjectured.

Conclusions

- A simple, very wide, hemispherical apse is extraordinary and there

is no equal with any of the British Norman churches.

- Comparable churches are either very early Norman (early conjectured

Canterbury, Jumiège and Bernay) or early Romanesque churches such as the

abbey of St Denis.

- Dating this foundation has been extremely contentious. A current

cathedral pamphlet states it was built around 1085 and is Norman. This has

been given without any evidence. Other later dates have also been given

without any supporting evidence. Why there is unsubstantiated dating in

the history of the cathedral is inexplicable.

- The dimensions of the foundation have an Anglo-Saxon metric of a

short perch (15 feet) and not a Norman rule of a long perch (18 feet). See

footnote 1.

- The mortar of the foundation

needs to be carbon-dated. It would be a relatively simple and cheap

project. Four top historians have called for this work to be done. Others

have expressed surprise it is not a priority.

[1] More detail is given in

the post, ‘It is short perch: historians, please note.’

[2] R. Willis, ‘On foundations of early buildings recently discovered

in Lichfield Cathedral.’ The Archaeological Journal, (1861), 18, 1--24.

[3] There is a problem with naming

the people Saxon or Anglo-Saxon (the preferred title in academic publications).

Based on surviving texts, early inhabitants of the region were commonly called englisc and angelcynn.

From 410 A.D. when the Romans left to shortly after 1066, the Anglo-Saxon term

only appears three times in legal charters in the entire corpus of Old

English literature and all are in the tenth century. It is used here because

Anglo-Saxon is understood despite being inaccurate.

[4] At

Hereford, there were three supposed apses in 1079 which changed between 1226

and 1246 to square chapels, but it is very uncertain.

[5] W. Rodwell, W. Revealing

the history of the Cathedral., Cathedral report in the Cathedral

Library. (1992). 24–34;

W. Rodwell, An interim report on archaeological excavations in the south

quire aisle of Lichfield Cathedral. Lichfield Cathedral report

in the Cathedral Library (1992) 1—8 and W. Rodwell, Revealing the

history of the Cathedral. Lichfield Cathedral report in the Cathedral

Library, (1994), 20–31.

[6] R. Krautheimer, R. Early

Christian and Byzantine architecture. (Harmondsworth: 1965).

[7] K. J. Conant, Carolingian and Romanesque

architecture, 800–1200. (New Haven and London: 1978).

[8] The old church, c. 475,

resembled Wilfrid’s church at Hexham according to Clapham (Oxford: 1930).

[9] S. M. Crosby, The Royal

Abbey of Saint-Denis from its beginnings to the death of Suger, 475–1151. (New

Haven and London: 1987).

No comments:

Post a Comment