Summary. Several

plague pandemics have killed residents of Lichfield; indeed, Chad died from the

disease. Probably two-thirds of the population died in the 14th century from

the Black Death. In 1553, with an estimated population of around 2000, Lichfield

was again gripped by the plague; and again in 1564 and 1593–4. On this last occasion it has been estimated upwards

of eleven hundred inhabitants died.

Facts on

plague.

- Caused

by the bacterium Yersinia pestis which circulates in rodents such as

rats, mice, marmots, gerbils, ground-squirrels and even cats. It

was passed by rodent fleas and itch mites. These were easily transmitted with

hand-me-down clothes and sleeping on a bed with others. Multiple occupancy of dwellings

often meant several generations died together.

- It

enters lymph nodes in the groin, armpit and neck causing painful swellings

called buboes, which can blacken If the buboes suppurate, the stench of the pus is overpowering.

- After

two days there is a fever, chills, headaches, body-aches, fatigue, vomiting.

70% of victims survive this stage.

- If

it enters the blood, it causes septicaemia, which can darken the skin. If it enters the lungs, it causes pneumonia.

Few survive this stage.

- These victims can pass on the disease in respiratory

droplets. Antibiotics

can cure if given within 24 hours of symptoms appearing. There are old vaccines

which the WHO does not recommend.

- It is a re-emerging disease with variants resistant to

antibiotics and most of the outbreaks are the lethal pneumonic form.[1]

Bubonic plague has led to three

major pandemics and many smaller ones. Before the sixth century there must have

been major pandemics, but they have not been attested.Old Testament Plague of boils, probably smallpox, in the Toggenburg, Switzerland,

Bible, 1411. Public Domain, Wikimedia.

First Pandemic was first recorded for Britain c. 549.[2] It

came from Egypt via the Middle East and Europe, lasted for more than 200 years,

and came to an end c. 750. This pandemic was also called the Justinian

plague after the emperor who ascended the papal throne when the plague started.

It killed seven known leaders in Ireland, some kings in Wales, Wigheard

archbishop-elect of Canterbury, several bishops including Cedd bishop of the

East Saxons, and Chad of Mercia. Various settlements ceased to exist in a

comparatively short time and the plague has been implicated. One notable example

is the Roman town of Viroconium (Wroxeter) which was thought to have had

several thousand inhabitants spread over 195 acres before the plague and within

two decades had shrunk to around 25 acres. A population reduction of sixty

percent in south-west Britain has been estimated. Bede described the pandemic

in 664.[3]

“In the same

year a sudden pestilence first depopulated the southern parts of Britain and

afterwards attacked the kingdom of Northumbria, raging far and wide with cruel

devastation and laying low a vast number of people. The plague did equal

destruction in Ireland”.

A plague outbreak in 686 killed all the monks in the monastery

at Jarrow except Ceolfrith and a young lad in his care that may have been

Bede.

In 672, it

was probably plague that killed Chad in Lichfield (Licitfelda). Bede described

his dying in the following way,[4]

Chad urged Owine and seven brothers to meet him in the church. He urged them

all to live in love and peace with each other and then announced the day of his

death was close at hand. “For the beloved guest who has been in the habit of

visiting our brothers has deigned to come today to me also.” Owine later heard

angels singing and Chad explained they were angel spirits coming for him. For

seven days his body became weaker before he died on March 2. He was buried in

the cemetery field near St Mary’s church and archaeology has shown this was a

site now under the nave platform in the cathedral.

Second Pandemic, also

known as The Black Death, was a variant of bubonic plague, and appeared to have

started in the late 1330s at two cemeteries near Lake Issyk-Kul in the north of

modern-day Kyrgyzstan, Central Asia. It passed with the Mongols giving siege to

a Crimean trading post and then quickly passed through Europe between 1346 and

1353 causing a great loss of population; 50 million has been mentioned. Proportionally

it was more destructive than the First World War with a third of the population

killed and in some places as much as two-thirds. In England its dates were c.1348-50.

It is generally considered to have entered England through the Dorset seaport

of Melcombe Regis, now Weymouth, during May or June of 1348, but the ports of

Bristol and Southampton[5]

have also been cited. Possibly as much as half the population was killed in the two years. Around 1300 the population was possibly close to 4 million, but by the Poll Tax in 1377 it was 2.5 to 3 million. Recurring bouts in 1361-2, 1369 and 1375 probably killed another 10-15%. That

means 60% of the population died within 30 years.[6]

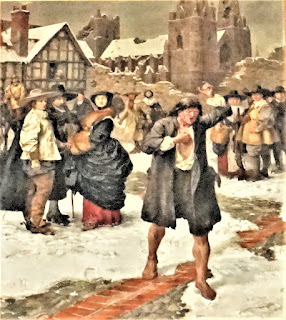

Black Death

in London. Wikimedia. Public Domain

A plague mortality figure of 40%

of priests within the Lichfield diocese has been calculated, though strangely, there

is no record of any death of cathedral clergy.[7] Clergy

probably unwittingly helped to spread the disease. Such mortality was close to

the national rate. Thirteen of the 17 dioceses kept registers of their

mortality and Lichfield’s stands out as the most complete. Bishop Roger

Northburgh, 1322–58, recorded 459 livings in the diocese and 188 suddenly

became vacant and this is assumed to be the result of plague-deaths. This

assumption has been challenged.[8] It

is likely some parishes were wiped out and the priest was forced to move away. It

has also been stated the plague started in Lichfield in April 1349 and was

virtually over by the end of October. Again, this seems unusual. The same

writer described how the bishop continued his work during the worst time of

July without panic or confusion. The national outlook was the disease was

baffling, its origin was said to come from supernatural causes and death was to

be expected. It was a pestilence of biblical proportions and caused fear.

The disease was a threat to life

over a long period of time.[9] England

endured thirty-one major outbreaks between 1348 and 1485, a pattern mirrored on the continent,

where Perugia was struck nineteen times and Hamburg, Cologne, and Nuremburg at

least ten times each in the fifteenth century. Venice endured twenty-one outbreaks to 1630. In 1553, Lichfield with an

estimated population of around 2000, was again gripped by the plague; and again

in 1564 and 1593–4. On this last

occasion it has been written that upwards of eleven hundred inhabitants died.[10] During

the Civil War, 1645–6, the city was again afflicted and 821 deaths were

reported in one year.[11] Then the Great Plague, 1665/6, struck in London,

killing 75,000 and later affecting other parts of England. It is known the plague occurred in Lichfield in

September 1665 and was blamed on a family giving lodging to travellers from

London. There

is no evidence it became endemic in Lichfield, which is surprising because this

was at a time of the great rebuilding of the cathedral. The last outbreak was in Malta in 1813. All the death tolls can only be estimations.

Mortality Paradox

Mortality

numbers for the 14th-century are 19th-century estimations. Pollen records in

England do not show a slow-up of agriculture, yet 90% of the population was

rural. Archaeology has not revealed increased mass burials. There was no disruption

of issue of coins. It is now considered the high levels of death have yet to be

substantiated.

The Third

Pandemic started in the Yunnan province of China in 1772, reached Hong Kong

in 1894 and then killed an estimated 20 million people in the world. Its

rate of spread was slow and mortality was around 1%, compared with fast

infection and up to 50% mortality in the second pandemic. It petered out in the

1940s, but sporadic outbreaks of plague have occurred since, such as in

California and Madagascar.

Consequences

·

It is said the Black Death interfered with building

of the cathedral, but the protracted period of poor weather and poor harvests

before the epidemic would also have affected work and labour supply.

·

It is known the plague increased bigotry. God’s

anger was interpreted as being caused by sinful people and blame fell on Jews,

friars, foreigners, beggars and even pilgrims. Folklore took over and it was infused

with prejudice.

·

The change of name from Licetfelda to

Lychfield was reinforced with preoccupation of death in a field.[12] There

was a widespread construction of shrines for the survivors to express gratitude

and perhaps guilt.[13] There

was a resurgence in appealing to the Virgin Mary for salvation.

·

New men of a younger generation filled the shoes

of those who died. They would have had a different outlook, worked in different

ways and were less beholden to feudal lords. Patrons were often new men and the

epidemic must have had a huge effect on the way they organised.

·

Recruitment was needed for the church and often

laymen joined the clergy. Pluralism in which members of the church held many

offices and gained much remuneration became common. It inevitably reduced

standards.

·

The population of Lichfield returned to its

pre-epidemic levels within twenty years; by 1664 it was estimated to be 2,500.[14] This was unusual, England did not recover to its

pre-plague population level until 1600.

[1]

Covid-19 killed just 1% before vaccination was given. Plague still kills 10%. A

Plague variant could be the next epidemic. See G. Lawton, ‘Return of the

Plague’, New Scientist. 28 May 2022, 48–51.

[2]

D. Keys, Catastrophe. An investigation into the origins of the Modern World.

(London: 1999). 114.

[3]

HE Book 3, Chapter 27. J. McClure and R. Collins, Bede. The Ecclesiastical

History of the English People. (Oxford: 2008), 161.

[4]

Ibid. Book 4, Chapter 3, McClure and Collins (2008), 176.

[5]

Henry Knighton, c. 1337-96, an Augustinian Canon suggested it entered England

through Southampton and reached London via trade routes through Winchester.

[6]

S. Thurley, ‘How the Middle Ages were built: exuberance to crisis, 1300–1408’. Gresham

Lecture 2011.

[7]

J. Lunn, The Black Death in the Bishop’s Registers. Unpub. thesis

University of Cambridge (1930) now lost.

[8]

J. F. D. Shrewsbury, A history of Bubonic Plague in the British Isles. (Cambridge:

1970).

[9]

A plague cemetery in East Smithfield, London, revealed skeletons with a peak

age of death of between 26 and 45, with a preponderance being male.

[10]

T. Harwood, The history and antiquities of

the church and city of Lichfield. (London: 1806), 304. The

incumbent of Alrewas wrote, “This yeare in the Summertime,1593, there was a

great plague in England in Divers Cities and Townes . . . and in Lichfield

their died to the number of ten hundred and odde and as at this time of wryting

not cleane ceassed being the 28 of November. This number is anecdotally

supported by the St. Michael's parish register which recorded an increase in

burials in May and June with very high figures in July and August.

[11]

Ibid, 306. Elias

Ashmole wrote a note listing deaths by streets for the year 1645 and recorded

821. Plague continued until 1647 and is thought to have killed one third of the

population of Lichfield.

[12]

See the post ‘Lichfield changed its name’.

[13]

D. MacCulloch, A history of Christianity. (London: 2010), 553.

[14]

C. J. Harrison, ‘Lichfield from the Reformation to the Civil War’, Staffordshire

Archaeological and Historical Society Transactions, (1980), 22, 122.