Summary. Much is now known how Early Medieval people of the 6th and 7th century lived, worked, ate, dressed, survived hazards, worshipped, kept law and order and improved health. It is presumed the early inhabitants of Licetfelda or Lichfield had similar cultural features.

An updated view of early 6th and 7th century Saxon[1] England (more accurately called Englisc) is one of a growing economy, improving communications, new understandings of religion, managed tribal projects and battles, a developing legal system, knowledge of where in the social hierarchy an individual stood and pledged loyalties to a warlord. Licetfelda (later changed to Lichfield) would contain a mixture of ethnicities, but this would be of little consequence. The terms Anglo-Saxon, Middle Angles (from Bede, book 1, chapter 15), Mercian or people of Licetfelda would be inconsequential. There was only recognition of their family and some loyalty to their ancestors and warlord. Reynolds expressed it as the natives in the time of Bede were not ‘English people,’ but an admixture of small to large polities, all with different origin-myths.[2]

The area

consisted of a very small group of hamlets until medieval times. In the “Great

Survey” of 1086 in the book known as The

Domesday Book, Staffordshire had an annual value of a mere 8 shillings per

square mile; only two other counties were poorer. This despite having a

relatively high number of settlements (342). Lichfield had a recorded

population of 9.9 households. This amounted to 42 villagers, 2 smallholders,10

slaves and 5 priests. There were 78 ploughlands.,10 lord's plough teams and 24

men's plough teams working in an area with 35 acres of meadow, 10 acres of

worked land, some woodland and much marsh with two water mills.

|

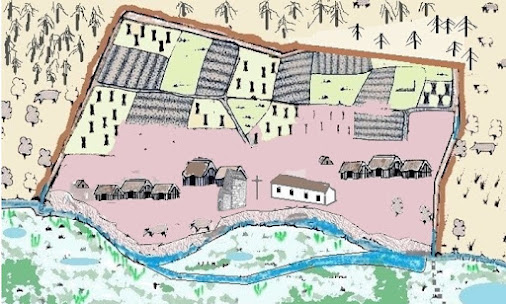

| Imagined view of what early Licetfelda looked like. |

Inhabitants managed the surrounding

trees for timber, burnt heather from the local heath for fuel and planted crops,

such as wheat, barley or oat (oat and wheat seeds were found in the

archaeological study south of the cathedral[3]). Flax

might have been planted in the wetter areas. Fields in Mercia were open and

could be large; some were divided into strips if they served a community. They

were measured in hides, but this was a loose and variable unit and simply meant

acreage which could support a family (estimated to be somewhere between 60 and

120 acres). Bread wheat was their staple food, but there was also dark rye

bread. Vegetables included garlic, leeks, onions, parsnips, radishes, shallots

and turnips. For planting crops an ard or scratch plough would be needed. They

would need a long scythe for clearing away bracken and heather. Intensive

manuring of the soil was important and crop rotation was understood. Very few

people in England ate large amounts of meat before the Vikings settled, and

there is no evidence that elites ate more meat than other people, a recent bioarchaeological

study has found.[4]

Ownership of land might be with the churl. They would most likely have owned a

few animals, particularly one or two oxen for ploughing, hens, geese and ducks,

and perhaps a cat or dog. It is also possible pigs, sheep and goats were kept.

If so, these animals would have been moved from wood to fields with the

changing seasons. The Old English feld in the name of Lichfield might be

an indicator of pig pasturing.[5] This

was a time when crop sowers were becoming interested in animal husbandry. They

would occasionally see horsemen.

The family might have had to

provide a food for a feast (honey, loaves, ales, cheese, birds, hams) to an

overlord, held outside near to their hamlet. It has recently been shown peasants

did not give kings gifted food as exploitative tax, but instead they hosted

feasts. Food lists for these feasts which have survived show an estimated 1kg

of meat and 4,000 Calories in total, per person.[6] An

examination of ten feasts has shown each guest (possibly more than 300) had a

modest amount of bread, a huge amount of meat, a decent but not excessive

quantity of ale and there was no mention of vegetables, although some probably

were served. The feasts were exceptional; there is no evidence of people eating

anything like this much animal protein on a regular basis.

For a long time, it has been

thought peasants had to pay a food tax, a form of tribute called feorm and the people producing it were

called feormers, a word which later

became farmers. It is now thought the giving of food for feasts was a one-off

event and served to connect farmers to the elite rulers. It was not an

obligation but gave a sense of communal connection. The first Mercian King

ruled from c589 and probably lived well away from most communities, but on rare

occasions turned up for a feast.

The average male stood at 172cm

(5 feet 8 inches) high and the average female was 157cm (5 feet 2inches)

according to skeletons found in graves. Dependence on low protein crops meant

young people did not attain full height until well into their 20s. A study of

residues of garments in graves concluded men wore coats, tailored tunics and

trousers.[7] Women wore a linen, tailored gown with long

sleeves that might have ended in leather cuffs and over this was worn a loose cloak

of coarser weave. They possibly had a veil. There were regional variations in women’s

clothes, but nothing is known on costumes for Mercia. Clothing was usually one

size for adults and one size for children. It was made to fit by tucking and

tightening with a belt. Women wore a kind of head dress or band held in place

with pins or on occasion with a buckle. A cloak might have had a hood. Animal

skins, such as otter, badger, pine marten, stoat and sheep, were worn by both

sexes with the fur on the inside. Shoes were also the same for both sexes and are

thought to be similar to those made by the Romans; namely, round toed, flat

soled and heavily laced. Only the rich could own elaborate brooches and pins,

and some even had embroided garments with gold thread. Saxon women wore

bracelets, necklaces and anklets. They might have hung useful items from a

belt. Men also possessed cloak brooches and possibly arm rings. The rings could

be copper alloy, or silver or at best gold for the rich. This jewellery varied

with fashion and area and it is unknown what was being worn in Mercia at this

time. Combs have been found which suggests hair was frequently groomed.

Considering the few Saxon finger rings ever found, it is unlikely the ordinary

Saxon would have one.

A variety of languages were used.

Chad, other priests and scribes writing the Gospels would know Latin. The

Anglo-Saxons would speak Old English (Ænglisc)

with a Mercian dialect. A few might have spoken in Brittonic, an insular Celtic

language. Indeed, Chad with his priestly training in Northern Ireland might

have understood this language.

Any habitation would have

resembled the excavated settlement at Catholme (7.8 miles, 12.5 km north-east

of Lichfield) in the Trent valley. This settlement is thought to have been

established in the 7th century and consisted of a series of

farmsteads and trackways. Enclosure ditches surrounded the houses and they

probably demarcated family groups. A single human burial was found at the

entrance to two enclosures and has been interpreted as an ancestral marker. The

trackways were a way of leading animals to the river. The ditches could also

have stopped animals wandering too close to the farmsteads and causing

problems. The idea of having ditches and trackways was relatively new and

depended on families cooperating to dig and maintain them.

Ditches and three early graves

were found in the archaeological investigation immediately south of the

cathedral.[2] The south choir aisle archaeology revealed early

Anglo-Saxon graves.

The people would have access to a

simple legal system organised from a Mercian stronghold somewhere in the Trent

or Tame River valley area. It would be a rudimentary family law with the

beginnings of human rights. The idea that others could be asked to give a

judgement on someone’s wrongdoing had started. Miscreants could do penance by

working for a church. Sickly and disabled children might also be cared for in

the church community. Women enjoyed many freedoms and some ran estates and

nunneries. Women exercised ownership of their household and intervened to help

other households. There are several accounts of kings listening to their wife

and being guided by her advice. Women were often equal in law to their husbands

and her sons. Everyone would know about the warlord, claiming to be descended

from Woden. Recognition of an elite ruling family in the area was relatively

new; their ancestry was often contrived. Separation between the privileged and

the poor was now beginning.

Boys would be trained in fighting

skills from the age of 7 and then receive their first weapons on reaching 14.

The most likely weapon would be a spear. He could then be called on to fight

for the warlord as a mercenary. If he received a sword, it would be accompanied

by oaths of fidelity and this would mark the attainment of manhood. The sword

would be special to the individual and might even receive a name.

There would be a path to

Lichfield and access to the church to hear the daily Divine Office of sung

prayers and chanted psalms with readings from the Bible given by a senior

cleric. The psalms sung by a precentor might have been accompanied by a

psaltery which was a 10 stringed, harp shaped instrument with a hollow,

triangular sounding box. Lyres have also been found that could have been used.

The church day was divided into 7 times for worship and if bells were rung each

time this gave nearby people an idea of the time in the day. No early Saxon

service book has survived, so it is unclear the order of a service. Maybe,

there was a diversity of services and it was not as rigid and regular as is

often supposed. A local pool or stream would be used for baptism and there were

many that were suitable.

Before the Synod of Whitby (663 or 664) the year had 12 lunar months and lasted 354 days. The names of the months were connected to customs associated with the time of the year and they varied regionally.

Names of months. From E. Parker, Winters in the World. A journey through the Anglo-Saxon year. (London: 2022), 15.

Every two years an extra leap month between June and July was added. After the Synod, the

Roman year of 365 days was followed and years later an extra day had to be

added to account for the missing quarter day. Only the two seasons of winter

and summer were recognised. Spring and

autumn seasons do not appear until the 16th and 17th

century. Bede considered winter started on 7 November and summer on 6 February,

but not everyone followed this. Those following the Celtic tradition started

their year on Halloween and later it became 25 December or Yule. The day

started at sunrise. For most people the time of the year would be known only

from phases of the moon, appearance of migrating birds, times when flowers

bloomed and fruited and when animals gave birth. Time would be a general

concept.

Inhabitants would be very aware

of changes in the weather and health and have some belief system to expiate

misfortune. Invocations and charms would be known and ways to foretell events

would be believed. Epidemics of a variant of plague swept through parts of England

at least four times in the seventh century. High mortality would have been

exacerbated by the poor general level of health. Life expectancy was probably

around 40 years with infant mortality being high and men generally living

longer than woman. Many female skeletons show ankle deformations consistent

with spending much time in the squatting position. High status individuals

lived just as long as low status people; there was not yet a spatial separation

of the privileged and so infections reached everyone. Age was measured in the

number of winters lived.

The climate was much colder that

it is today, but it started to get warmer after the 7th century.

Their rectangular timber framed dwelling perhaps had a heather brush roof; very

thick and strong to bear the weight of snow. At West Stow Saxon village,

Suffolk, a ‘stuffed thatched’ roof with a base layer of gorse into which straw was

stuffed has been found to give a sturdy roof and might have been used in

Mercia. The floor was probably raised up to be above the damp ground, but how

this was generally done is still unsettled. Most ornaments would be fashioned

from wood, but the churl probably knew of a smith in the area to obtain forged

goods. Goods would be bartered and so a sense of relative values would be

known. Some might have been able to afford glass bowls for eating and drinking;

the glass most likely being recycled Roman glass. There might have been some

trading with travellers. One particular item that would be sought was a quern

stone for grinding seeds. Another would be flint for cutting. Other extras

could be bought at wics or trading

centres and for Mercia they are not identifiable. All the 30 plus productive

trading wics known were spread across eastern England. Traded goods would have

travelled along the river Trent from the wics in Lincolnshire, but where they

were offloaded is unclear; Tamworth is a guess, Burton another.

Red and roe deer, wolves, boar,

beavers and otters would occasionally be seen. People would have heard old

stories of the extinct lynx and brown bear. They might see once in a lifetime a

wildcat. Black rats, wood mice, shrews and mosquitoes were pests. Foxes,

badgers, shrews, weasels, red squirrels, hedgehogs and pine martens were

commonly seen. Hare would be evident on fields, but not rabbits. Common birds

were sparrows, swallows, martins, crows, rooks, ravens, starlings, jackdaws,

pigeons, buzzards, red kites, herons and cranes (the carpet page of St Chad’s

gospel shows entwined, three-legged birds that resemble cranes). In 671, there

was a “great mortality of birds”, presumably because of a very cold winter. The

heathland would have grouse, quail, partridge and possibly pheasants. There

would be little hunting of animals unless the churl could join with others to

assist, in which case hounds were used for chasing. January was the favoured

time for hunting wolves. They would set snare traps for small animals. Local

streams could provide eels and trout. Boys dug foxes out of their holes and

hunted hares.

7th-century medicine

The common view of early medicine is it consisted of herbal potions, magical practices, superstitious beliefs, invocations and charms based on strange ideas of how the body worked. The Lacnunga, British Library Harley MS 585 early-11th century, described remedies requiring chants of particular words and actions that had to be repeated. A carbuncle required a chant sung 9 times that started with the Lord’s prayer. An illustrated Old English herbal, British Library Cotton MS Vitellius C III early-11th century, advised parsley for a snakebite.

The central concept was a doctrine of four humours[8] which when in balance and harmony gave a healthy body, but any disruption led to disease. Disease was primarily caused by internal disequilibrium, but also affected by the seasons of the year and natural rhythms of the universe[9]. Blood circulated like the tides. Added to this was the view of the body being invaded by ‘alien matter,’ evil spirits and sometimes the wrath of God.[10] Medical care was available in monasteries and often prayer and pilgrimage were seen to be all that was offered. Primitive medicine was always irrational and limited. However, that is not the whole picture; there was much that helped and sometimes the unwell were cured. Consider the following:

1. There was a body of lay practitioners, mostly in monasteries, available to treat the general population. They were called in Old English, laece, translated as a leech or physician. A doctor was also a medicus[11]. They were expected to deal with all kinds of illness and injury and a host of symptoms with causes beyond anyone’s comprehension. [12] St John of Beverley attended several unwell people and Bede described their treatment.[13]

Page from Bald’s Leech book, written c. 900–950, British Library Royal MS 12 D XVII. Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain. The Leech book contains innumerable prescriptions for a bewildering variety of illnesses, injuries and mental states.

2. The monastic practitioner, according to Bede,[14] had a centre, hospitale, for their practice where sick people were taken. This centre also provided accommodation for travellers, pilgrims and those requiring hospitality. Presumably, one was located at Lindisfarne, and perhaps also at Licetfelda.

3. Medicine was a subject for study. St Aldhelm mentioned medicine as one of the subjects taken at the school founded at Canterbury by Archbishop Theodore in c .670.[15] According to Bald’s Leechbook, mid-10th century, remedies were drawn from early Latin and Greek texts such as by Alexander of Tralles, died c. 605, and Anglo-Saxon physicians known as Oxa and Dun.

4. The leech charged fees for their services known as a laece-feoh, leech fee.[16] The usual outcome was the making of certain compounds with the hope of relieving symptoms.[17] There is evidence of making a thoughtful prognosis. Bede described a young man who developed a swelling on his eyelid which progressively grew bigger. Poultices had been applied without success and some leeches advised lancing the swelling, but others disagreed fearing complications.[18] A recipe for an eye salve in Bald’s Leechbook, mid-10th century, has been shown to be effective against antibiotic resistant bacteria.

5. Treatment of fractures occurred. Bede described several people sustaining fractures and their treatment. In the Life of Wilfred, a young mason named Bothelm fell from the top of Hexham church and broke various bones and dislocated some joints. Physicians were called in who immobilized the fractured limbs with bandages.[19] Bede tells the story of Herebald who was riding in the company of John of Beverley when he fell off his horse and fractured his thumb and skull. John called for a surgeon who bound up the injured man's skull.[20]

6. There was a rudimentary understanding of disease spread by contagion. Archbishop Theodore at the Council of Hertford, 672, eight years after the death of Cedd at Lastingham, forbade monks from travelling from one monastery to another.[21] This was possibly a response to stop the spread of plague, though there could have been other reasons. When Chad became ill, he told his brothers he had been visited by ‘the beloved guest who has been in the habit of visiting our brothers.’[22] The guest could have been a rodent carrying fleas as a vector for bubonic plague (blefed).

7. Skin diseases due to malnutrition, vitamin deficiency and lowered vitality were common. It is doubtful whether the remedies prescribed would have had much effect although in one case, at least, a recipe for scabs on the skin which contained tar might well have proved beneficial.[23]

8. Early histories of plague in Europe usually remarked on the dirtiness of Anglo-Saxon life. Accumulation of waste in the dwelling and street, poor disposal of human and animal waste, overcrowding and poor ventilation are cited as reasons for the easy spread of disease.[24] This poor state has not been substantiated and is probably another example of maligning the Anglo-Saxon, especially by comparison with earlier Roman times. It does not account for pestilences being highly contagious.

9. Palaeopathology has given some indication to the sort of ailments the leech might be called upon to treat. Osteoarthritis was a common joint condition and has been found in much skeletal material from Anglo-Saxon cemeteries. Dental, alveolar disease and fracture of the ankle have been frequently encountered. Less common conditions include osteochondritis dissecans, congenital dislocation of the hip, pyogenic arthritis of the humerus and even leprosy.[25]

The conclusion is many desperately searched for a miracle cure and whilst most remedies were useless the leeches provided some measure of comfort for the sick. Indeed, the practitioners carried out their work with at least some regard to the ethics and morality of their calling.[26] Few doubted their worth.

[1]

There is a problem with naming the people Saxon or Anglo-Saxon (the preferred

title in academic publications). Based on surviving texts, early inhabitants of

the region were commonly called englisc and angelcynn. From

410 A.D. when the Romans left to shortly after 1066, the term only

appears three times in legal charters in the entire corpus of Old English

literature and all in the tenth century.

[2]

S. Reynolds, ‘What do we mean by Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Saxons?’ Journal of

British Studies (1985), 24, 395–414.

[3]

M. O. H. Carver, ‘Excavations

south of Lichfield Cathedral, 1976–1977’ South Staffordshire Archaeological

and Historical Society Transactions, 1980–1981, XXII (1982), 38.

[4]

S. Leggett and T. Lambert. ‘Food and Power in Early Medieval England: a lack

of (isotopic) enrichment’. Anglo-Saxon England, (2022), 1.

[5]

D. Turner and R. Briggs, ‘Testing transhumance: Ango-Saxon swine pastures and

seasonal grazing in the Surrey Weald, Surrey Archaeological Collections, (2016),

189.

[6]

T. Lambert and S. Leggett. ‘Food

and Power in Early Medieval England: Rethinking Feorm’. Anglo-Saxon

England, (2022), 1.

[7]

K. Brush, Adorning the dead. The social significance of early Anglo-Saxon

funerary dress in England (Fifth to

Seventh centuries A. D.), Unpub. PH. D. dissertation, University of

Cambridge.

[8]

The four humours affect temperament: Blood makes a man of goodwill, simple,

moderate, reposeful and sturdy. Red bile makes a man of even temper, just, lean

of figure, a good masticator of his food, and of strong digestion. Black bile makes

a man irascible, greedy, avaricious, sad, envious and often lame. Phlegm makes

a composite type, watchful, introspective and growing early grey headed.

[9]

H. M. Cayton, ‘Anglo-Saxon Medicine within its Social Context.’, Durham theses,

Durham University. (1977) Available at Durham E-Theses Online:

http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1311/

[10]

Apostasy and immorality, usually of a sexual kind, were often given as reasons.

[11]

J. McClure and R. Collins, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

(Oxford: 2008), Book IV, Chapter 19, 204.

[12]

S. Rubin, ‘The medical practitioner in Anglo-Saxon England’. Journal Royal College

General Practitioners, (1970), 20, 63.

[13]

Ibid, Book IV, Chapters 2–5, 237–241.

[14]

McClure and Collins (2008), Book IV, Chapter 24,

217.

[15]

J. G. Payne, English Medicine in Anglo-Saxon Times, (Oxford: 1904), 15.

[16]

A 12th-century comment of William of Malmesbury in ‘Life of St Wulfstan’

[17]

S. Rubin (1970), 65.

[18] McClure and Collins (2008), Book 4, Chapter

32, 232.

[19]

B. Colgrave, The Life

of Bishop Wilfrid by Eddius Stephanus. (Cambridge: 1927), Chapter 23, 47.

[20] J. McClure and Collins (2008), Book 6, Chapter 6,

243.

[21]

Ibid, Book IV, Chapter 5, 181.

[22]

Ibid, Book IV, Chapter 3, 176.

[23]

W. Bonser, The medical background of Anglo-Saxon England. A study in

history, psychology and folklore. (London: 1963), 375.

[24]

A. Hirsch, Handbook of geographical and historical pathology. (London:

1883), 1, 522.

[25]

For detailed descriptions of diseases in Anglo-Saxon populations, see the work

of Calvin Wells, e.g. Bones, Bodies and Diseases, London 1964; and D.

Brothwell, e.g. "Palaeopathology of Early British man", J. Roy.

Anthrop. Inst. 1961, 91. 318-44 and Digging up Bones, London 1963.

[26] S. Rubin (1970), 70.