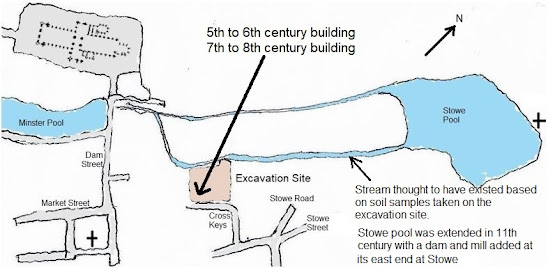

Summary. Archaeology at Cross Keys, 2005-6, revealed two early buildings, one possibly 6th or 7th-century and another 8th-century. Was this an early settlement in Lichfield?

A plot of known Anglo-Saxon settlements on the map of England shows a frontier line running north-south along the Trent washlands of south-west Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. There are many settlements to the east of this line and very few to the west, Catholme is exceptional. Yet coins and graves have been found west of the line. This suggests in the 6th and early 7th century Lichfield would have been on a marginal border and the inhabitants pioneer colonists.

Several reasons for this ‘invisibility

of settlements’ in the West Midlands have been given. Perhaps, by the beginning

of the 7th century people had not migrated across middle England and settled.

Perhaps, their dwellings were unlike the timber buildings of the east (post,

post in trench and sunken featured buildings) and they left no trace in any

excavation; instead, they were erecting turf, cobble or loose stone and rubble

buildings. Did they prefer to move around in temporary buildings (including

tents) which could be dismantled and moved on? Have soil stains, ground

depressions, floors and even stake holes not survived so well in the wetter,

western climate? It has been argued settlement patterns were largely a

consequence of environmental factors, such as the influence of climate, soils

and hydrology, and the patterns of natural topography.[1] The

drier east was more conducive to survival. It is no surprise for a paucity of Early

Medieval settlements in the West Midlands and particularly around Lichfield.

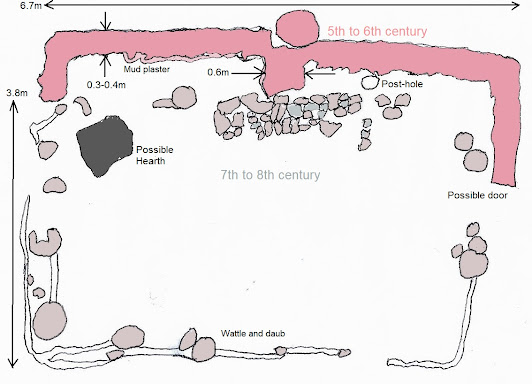

Before a two-storey car park was

built on Cross Keys Road, an excavation was conducted at the end of 2005 and

into 2006. Two remarkable buildings were found. The north end of a

two-chambered building was uncovered around a rectangular pit around 0.4 m

deep. Walls contained Roman masonry with yellow mortar attached and bonded

together with boulder clay. A twig in the mortar was carbon dated to 89–334.

The floor contained rye and wheat grains and there were traces of barley, small

mammals and fish bones. A twig in this detritus was carbon dated to 436–636.

Charcoal was also found dated to 604–683. Mud plaster on the walls, 10 mm

thick, suggested it was possibly a dwelling. The grains suggested it might have

become a store and the charcoal hints it was destroyed by fire.

|

| Cross Keys excavation site |

On its south side was a 7th to 8th-century timber building around a new pit and cut deeper into the ground. Post-holes suggested a dwelling similar to those found at Catholme, but larger. Supporting posts were in the corners and along the middle line of the building. Wattle and daub looked to have been used for infill. A twig found near the wattle was dated to 688–868.

|

| The upper building is 5th to 6th-century, or even later, but has stones with Roman plaster. The lower building is 7th to 8th-century. |

Sargent[2] using notes from the archaeologist,[3] described the early building as unique in Britain. Being stone built and mud plastered suggested a monastic cell, however, the position of the putative doorway, little wear of the floor and its sunken pit does not entirely fit. Sargent compared it with the sunken crypt at Repton and even the possibility it was a funerary mausoleum. It might have pre-dated the early church. Sargent reappraises the many conjectures on how the polyfocal area of Lichfield grew from early times. He noted[4] that early to mid-Anglo-Saxon (Early Medieval) pottery sherds, 5th to 9th-centuries, were found during excavation of a site to the north of Sandford Street supporting an early medieval occupation around the northern end of Bird Street.[5]

[1]

T. Williamson, Environment, Society and Landscape in early medieval England:

Time and Topography. (Woodbridge: 2015).

[2]

A. Sargent, ‘Early medieval Lichfield. A reassessment’. Staffordshire

Archaeological and Historical Society Transactions, (2013), 1–32.

[3]

N. Tavener, Cross Keys Car Park, Lichfield, Staffordshire. Level 3 archive

report on an archaeological excavation and watching brief. (unpub. report, Nick

Tavener Archaeological Services) (2010).

[4]

See Sargent (2013), 5.

[5]

K. Nichol and S. K. Rátkai,

Archaeological Excavations on the North Side of Sandford Street, Lichfield,

Staffordshire, 2000 (unpub.report, Birmingham University Field Archaeology

Unit) (2002), 14.