Summary. After Civil War destruction much remained in a poor state for nearly two centuries. Clergy and architects directed a comprehensive repair in the second half of the 19th-century. It is now a Victorian Gothic Revival building.

In the

late-18th and early-19th centuries cathedrals and churches were in an

uncertain, frequently precarious state[1].

They were poorly lit, cold and often closed during the day. Yet many were

wealthy having landed estates around the church usually owned by clergy. Priests

appeared to be privileged, remote and have little relevance to the Church. It

needed The Duties and Revenues Act of 1840[2] to

change matters and carry out an extensive overhaul of cathedral organisation

and finances. One revision was now a dean and four residential canons

constituted a reduced Cathedral Chapter. Funds were diverted, dioceses altered

and extensive restoration undertaken.

Like many

cathedrals, by the late-18th to early 19th-century Lichfield Cathedral was in a

moribund state. Reformation had stripped its wealth and the Civil War had

wrecked it. Almost the whole interior, floor to ceiling, was covered in

‘uniform, dead, yellowish whitewash many coats thick’.[3]

For two centuries the appearance of the inside of the cathedral had remained

little changed[4]

from the Parliamentary army despoliation and the subsequent minimal internal

restoration.[5]

There was very little in the transepts and, apart from the font up a corner,

nothing in the nave. Services were held in an isolated choir; a dark, cold

church within the outer cathedral. The choir aisles were unlit and never used.

A heating flue passed down the middle of the choir, but it rarely worked. Any casual

visitor could hear worship, but not see it. Considerable stonework needed

urgent repair and much was in a shoddy state. In the 1851 religious census the

cathedral had 395 seats for worshippers and an average of 200 attended the

morning service and 210 in the afternoon. This was less than half the

attendance of St Marys in the Market Square.

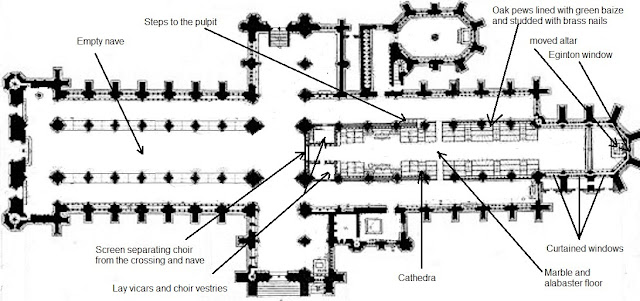

Plan of the

cathedral, 1820.[6]

AI rendition of the view of Lady Chapel, being used as the chancel, Britton 1820. Note the absence of statues in the niches.

AI rendittion of the view of Choir, Britton 1820, Note the lack of statues and wall decoration. When the plaster was removed cinque-foil decoration was revealed.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert visited Lichfield in 1843 and passed by the front of the cathedral.

Between 1856 and 1894, extensive

restoration of the cathedral was undertaken, initiated by Canon John

Hutchinson, agreed by Deans Henry Howard and Edward Bickersteth and overseen by

the architects George Gilbert Scott,[7]

his son John Oldrid Scott and grandson Giles Scott. The restoration was after

much deliberation, argument, and consultation from many architects and clergy. Worship

was made open to all, music improved and preaching enhanced with the opening of

the Theological College in 1857. Visitors were welcomed. Canon G. H. Curteis

preached a sermon in February 1860 on ‘Cathedral Restoration’ and claimed the

cathedral was again a place where pilgrimage occurred. He said every modern

appliance and the highest modern skill was being used to restore the

cathedral’s ancient beauty. The extensive changes were recorded by Canon John

Lonsdale.[8] He

wrote in 1895 the cathedral had gone through a complete revolution so that the

building would hardly be recognised from that which stood forty years

previously.

The

restoration

From 1856, workmen, around 20-30, laboriously chiselled

off the whitewash (at Wells cathedral it was called the Great Scrape), removed considerable

underlying plaster and began to repair much of the stonework. Brick flues carrying

hot air were built under the whole floor. During this work historic foundations

of the first two cathedrals were found and then surveyed and analysed; see the

post ‘Why the second cathedral must be Early Medieval.’ Old tilework was

discovered. New floors were laid. Woodwork was replaced. Almost all the windows

were altered and new glass installed. Some windows had brick infill removed. New

statues[9]

were added both internally and on the west front and east end. After scraping

the choir vaulted roof, bands of red, blue and green paint were uncovered. A

minimal amount of new paintwork was added. A larger, modern organ was

installed. A metal screen, designed by Scott, between the choir and crossing

was much discussed and finally manufactured by Francis Skidmore of Coventry. Skidmore

was asked, 1860, to make two large brass standards holding gas lights for the

end of the choir and six more brass standards for the choir. This was the first

introduction, completed 1862, of gas lighting into the cathedral.

The choir in 1858. All furnishings have been removed. The scaffolding was for placing new statues on the walls.

AI rendition of the choir in 1860 with statue niches on the walls, but not yet statues.The choir in 1860. Wyatt’s marble paved floor is being replaced by Minton tiles. The mobile scaffold was used to remove the limewash from the ceiling and walls.

The possibility of making the entire nave roof out of stone was considered, but difficulties of weight and wall support prevented this happening. A new reredos was added to the end of the choir and before Chad’s shrine with most of the work done by John Birnie Philip. It has statues made from alabaster obtained near Tutbury. They are not shown in the proposed drawing.

Drawing by G. G. Scott of proposed reredos for the high altar.

The

section behind the altar table was given red marble[10]

from Newhaven, Derbyshire. Inlay included red jasper, blue john and malachite

green stone.[11]

The tiles, designed by Scott, were given by Minton of Stoke and the inserted roundels

were innovative.[12]

Woodwork, including the bishop’s cathedra, was executed by William Evans[13]

of Ellastone.[14]

A new pulpit in the nave was made by

Skidmore. Iron grilles at the end of the choir aisles were made by Atterton of

Lichfield. The eagle lectern was by John Hardman. All this was a celebration of

Midland’s craftsmanship. A new font designed by William Slater and executed by

James Forsyth was placed in the north transept. The sedilia canopies by the

current reredos were formed from stonework obtained from the early screen and

reredos of the cathedral with considerable repair necessary.

Substantial repair to the Chapter House roof was needed. Many of the stone heads inside were refurbished. The altar platform, or dais, at the east end was removed. Restoration of the consistory court revealed early stonework which baffled Scott and has since been the object for fanciful speculation, see the post ‘Rooms south of the choir.’ The current library was constructed in the treasury room above the Chapter House and an adjacent chapel and its contents sorted, see the post ‘Old Library.’ The south transept monuments in remembrance to fallen soldiers were reordered and a metal grille separating the chapel was installed. Bishop Selwyn’s monument on the south side of the Lady Chapel was completed in 1892.

AI gen. Bishop George Augustus Selwyn in Polynesia.

Early photograph of Selwyn’s monument

A new reredos in the Lady Chapel was made at Oberammergau and accepted to show Tyrolean figures, see the post ‘Lady Chapel and Sainte-Chapelle’. The stonework of the Lady Chapel windows was comprehensively repaired together with rebuilding buttresses and southside chambers. This was repeated with the Chapter House windows. Finally, the central tower and spire had to have considerable restoration. During this work it was found that stonework in the transepts needed rebuilding. Indeed, a buttress against the north transept collapsed.

This is an abridged list of changes made to mostly the

interior and shows the Victorian clergy and builders improved and conserved

almost the whole building. The cathedral had a fundamental reconstruction. The

notion the cathedral was returned to how it more-or-less looked in the Middle

Ages has been a common abstraction, but is more wishful-thinking than reality. However,

the wonder is that from the ashes of the Civil War a beautiful (Victorian)

church has been recovered. According to Cobb[15]

the recovery from 1856–1908 cost £98,000 (today equal to £10.5 million, but

this must have been a minimum cost not accounting for donated materials and

consultation).

[1]

J. Morris, A People’s church. A History of the Church of England. (London:

2022), 140.

[2]

Known as Ecclesiastical Commissioners Act 1840, In fact, there were many

further Acts until 1885. There were many in the church who opposed the measures,

see J.L.K. Bruce, ‘Speech Delivered in the House of Lords on Behalf of the

Deans and Chapters Petitioning Against the Bill, 23 July 1840.’ (Harvard:

1840). It was promoted by Robert Peel who wrote, ‘that such was the state of

spiritual destitution in some of the largest societies in this country, in some

of the great manufacturing towns, that it could not be for the interest of the

Church of England to permit that destitution to exist without some vigorous

effort to apply a remedy.’

[3]

Ibid, 7. In 1666 and 1691, contracts were given to re-whitewash the whole of

the interior walls; this being easier than removing the original layer.

[4]

The architects James Wyatt,

1788-95, and Sydney

Smirke, 1842-46, made small changes and some restoration, but arguably kept

the cathedral as it was post-Civil war. Pews were removed and the nave

brick floor was replaced with Hopton stone slabs.

[5]

Restoration had concentrated on the frame of the cathedral, especially

repairing almost every roof.

[6]

J. Britton,The history

and antiquities of the See and cathedral church of Lichfield. (London: 1820),

75.

[7]

Largely known as Sir Gilbert Scott. Simon Jenkins called him the 'unsung

hero of British architecture'.

[8]

J. G. Lonsdale, ‘Recollections of the work done and in upon Lichfield

Cathedral, 1856–1894’. (Lichfield: 1895), 1–38.

[9]

There were no statues in the choir before 1856, but they had been mentioned in

the 18th century and used to model the current figures.

[10]

Also known as ‘Duke’s red’ from the Chatsworth estate. It was a rare form of

marble.

[11]

From the Derbyshire mines. Derbyshire was part of the diocese until 1906.

[12]

Herbert Minton donated tiles to over 150 churches in the Lichfield diocese by

1858. Upon his death in 1858 he was succeeded by Colin Minton Campbell who

donated the Minton tiles to the cathedral in this year.

[13]

George Eliot’s uncle. Some state it was her cousin (H. Snowden Ward, Lichfield

and its cathedral, (Bradford and London: 1892). It was reputed William

Evans was the inspiration for Seth in her book ‘Adam Bede’.

[14]

Woodwork carvings include figures of the Apostles with their emblems. On the

right-hand side of the choir are: a figure of a king and a bishop with angels

at the sides, then follow St Andrew with a transverse cross, St Jude with a

club raised, St Philip with a cross, St Thomas with an arrow, St Bartholomew

with a knife and St Simon with a saw. The carved panels at the ends represent

Saul's jealousy of David, Miriam with a timbrel in her hand, Saul's daughter

despising David and alternate groups of angels playing musical instruments. On the

left-hand side of the choir is a figure of a bishop and a king with angels at

the sides, then follow St James the Great with a pastoral staff, St Matthew with

a box, St James the Less with a club, St John the Evangelist with a cup, St

Peter with the keys and St Paul with a sword. The carved panels at the ends

represent Jephtha's rash vow, David playing before Saul and alternate groups of

angels playing musical instruments. Taken from J. B. Stone, A history of Lichfield Cathedral: from its foundation

to the present time. (London: 1870),

68–9.

[15]

G. Cobb, English Cathedrals the forgotten centuries. Restoration and change

from 1530 to the present day. (London, 1980), 238. Cobb quoted J. E. W. Wallis

and O. Hedley (Pitkin: 1974)), 24.

No comments:

Post a Comment