Summary. Small amounts of stonework in the choir area were described in 1861 as Early English in architectural style. This area is thought to have been reordered before construction of the cathedral in order for worship to continue. Precise dating has been equivocal.

Robert Willis,[1] 1800–75, an architectural historian, visited Lichfield Cathedral for two days in August 1859 wrote his seminal conclusions in 1861. He identified the earliest part of the standing cathedral as the choir area, and stated it had Early English architecture.

|

Style |

Date |

Kings |

|

Early

English |

1189–1272 |

Richard

I (1189–99, John (1199–1216, Henry III (1216–72) |

|

Decorated |

1272–1377 |

Edwards

I (1272–1307), II (1307–1327) and III (1327–1377) |

|

1377–1547 |

Richard

II to Henry VIII (1377–1547) |

Architectural periods from J. H. Parker, ABC of Gothic Architecture, (Oxford and London: 1881). Dating for the styles of architecture are putative.

Some architectural historians fix Early English with a

shorter time-span of 1180–1250 and that might apply to the cathedral. It was a

transitional period from the heavy, monumental Norman way of construction to

the lighter, decorated stonework that followed.[2] Features of Early English that

applied to the choir are:[3]

·

lancet windows, that were long narrow windows

with pointed arches and no tracery. Later came ‘plate’ tracery, so-called

because the openings were cut through a flat plate of stone.

·

columns or piers composed of clusters of

slender, detached shafts, which ascended to the vaults above.

·

decoration included mouldings which were deeply

cut. There is dog-tooth ornamentation around the arches.[4]

·

the abacus or capital at the top of the columns

was circular.

Similar double chevron on the east wall of St David’s cathedral, 12th-century.

· the arcades in the nave occupy the lower half of the side wall. The upper half being divided equally between a triforium and clerestory. There is symmetry.

·

sculptured figures of large size were used, and

placed in niches with canopies over them.

|

| Willis's interpretation, 1861, of Early English in the choir. |

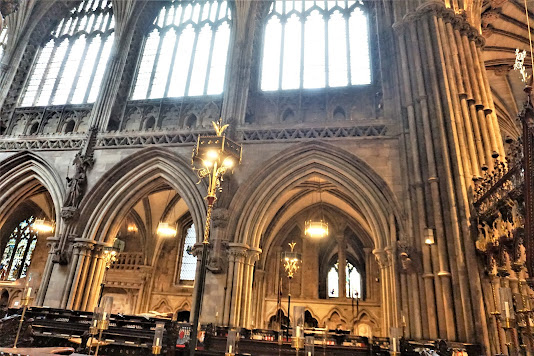

North side second bay of the choir showing Early English piers. The clerestory above is Decorated with Perpendicular panelled windows.

He found the 3rd piers were Early English on the west side

and Decorated on the east side. Clearly this is the ‘join’ between the two

phases of construction.

Drawing in ‘Lichfield Cathedral’ in The Builder, 1891, of the change in piers from Early English to Decorated with the 3rd piers split on two sides.

Plinths

Throughout the cathedral are

piers with plinths moulded in an Early English style that has a hollow roll

known as a ‘water-holding’ base.[10] This deeply cut roll

echoed the deeply undercut moulding on the capital. They are very different

from the simpler, round rolls of earlier piers and the elaborate ‘triple rolls’

of later Decorated piers.

|

| Second south pier in choir showing clustered shafts around the pier, with some decoration on the capital and a ‘water-holding’ plinth. This pier is typically Early English. |

On trying to date the

architecture Willis stated, “The present choir is so early in its details that

it must have been commenced (or considerably reordered?) near the beginning of

the century,” that is, the 13th-century. The investigation and conclusion were

repeated in the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1861;[11] However Willis was

uncertain and called his visit ‘a curious investigation’.

Willis wanting to fix a timeline

to the cathedral found it difficult to give dates for the revealed second

cathedral foundation and for a foundation of a rectangular chamber under the

presbytery. He was cautious on the timeline for the different levels of the

central tower. His dates for the rest of the cathedral have more-or-less been

accepted, but they too are approximations.

Anomalous font

In the floor of the presbytery was found a very large,

square, font.[12]

Willis did not see this (?) and the font has since disappeared.

Font drawing by John Hamlet 1854. It had been reddened and

cracked by fire.

Font drawing by John Hamlet 1854. It had been reddened and

cracked by fire.

Placing an unwanted font under

the high altar suggests it had historic value. It could therefore have been

more ancient than the dates affixed to the standing cathedral, see the post ‘Dating

the cathedral’. If it is still under the high altar floor and could be

re-found, it would, if datable, give insight to the second cathedral.

Rodwell’s view

Rodwell saw it necessary to split the Early English period

into three (c. 1200–20, c. 1220–30 and c. 1230–40) to

explain the rooms on the south choir aisle.[13] He thought construction

was continuous with the choir, crossing tower and transepts, but in that order.

This is a challenge to confirm and ignores King John’s Interdict, March

1208–July 1214, when all cathedral activity supposedly stopped. There is no

reason to ignore the notion that work continued on all three areas at the same

time.

The conundrum of the roof

In 1243, Henry III commissioned Walter Grey, Archbishop of

York, to expedite the works at St George's Chapel, Windsor, and to construct a

lofty wooden roof, like the roof of the new work at Litchfield. It

was to appear like stone work, with good ceiling and painting.[14]

So which roof was Grey to model his wooden roof? It would be logical to assume

he is modelling from a wooden roof at Lichfield. Willis thought there was

originally a wooden roof above the south transept and this was the model.[15]

Wall shafts under the vault in the south transept have on their top an Early

English abacus and above that a later abacus in Perpendicular style suggesting

the stone vault roof was added considerably later than when the lower walls

were built.[16],[17]

Rodwell thought the choir had originally a wooden roof. He wrote, “The

buttresses along the aisles were rebuilt and were adapted to receive fliers

from the high roof of the choir. Thus, the choir was undoubtedly vaulted at

this stage, although perhaps in timber rather than in stone. Surely this is

what Henry III admired in the late 1230s and ordered its replication at Windsor

in 1243.

Clifton thought the date, 1240s, would better suit a timber

roof above the transepts than the choir. There is in all this conjecture an

ignoring of the phrase to appear like stone work. Could this mean Grey modelled

from a stone, vaulted roof at Lichfield, but had to construct the roof at

Windsor in timber? The current roof in St George’s Chapel does not resemble any

roof at Lichfield. Three-quarters of the nave roof is in timber and made to

resemble stone work. Having an earlier timber roof and then soon after changing

to a stone roof seems unlikely, though not impossible. It is another

uncertainty.

[1]

R.

Willis, ‘On foundations of early buildings

recently discovered in Lichfield Cathedral’. The Archaeological Journal, (1861),

18, 1–24.

[2]

The general view is the crossing tower, first three, western bays of the choir,

the chapel on the south side of the choir and the south transept are Early

English. There are also indications parts, such as the vestibule and

chapterhouse, on the north side of the choir aisle are also Early English. The

north transept is probably late Early English, but has indications of also

being early Decorated.

[3]

Taken from B. F. Fletcher. A History of Architecture on the Comparative

Method for the Student, Craftsman, and Amateur. 5th ed. (London: 1905).

[4]

The simplest form of chevron was introduced to Britain between the years

1120–30, according to A. W. Clapham, English Romanesque Architecture after

the Conquest. (Oxford: 1934), 128.

[5]

There is a similar moulding around the north doorway of Llandaff Cathedral and

in the Glastonbury Abbey ruins. There is a Norman moulding called a Lozenge,

but it does not have the middle line of stone running through the chevrons.

[6]

Willis (1861), 11–13.

[7]

The plinth can be a flat, square stone originally intended to keep

the bottom of wooden pillars from rotting. Willis did not rule out the Early

English piers were originally wooden. Willis (1861), 4 footnote.

[8]

The Early English plinths and portions of the flat buttresses to piers on the

south side aisle were observed again by J. T. Irvine in April 1880 and reported

in The Archaeological Journal, (1880), 37, 214. Irvine’s drawings

titled ‘Plinths and ancient buttresses of south aisle of quire, Lichfield

Cathedral, laid open April 22, 1880’ are in Staffordshire Record Office,

LD30/6/2/55.

[9]

Willis concluded, “The buildings, although showing differences of detail and of

construction which prove they were erected at considerable intervals, and under

different architects, do follow the same general design, and were they dated

would greatly elucidate the chronology of the Early English style.”

[10]

H. Braun, An introduction to English Medieval Architecture. 2nd edition

(London: 1968), 271, Fig. 201. The water-holding aspect is fanciful; it is more

likely to hold dirt.

[11] R. Willis, an address to the Archaeological Institute.

The

Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Review March. (1861). 210, 296–300.

[12]

The font was 1.4 m square (4 feet 6 inches square) and 0.6 m thick (2 feet).

The cavity was 1 m diameter (3 feet 3 inches) and had a rebated lip suggesting

it had a cover.

[13] W. Rodwell, ‘The

development of the choir of Lichfield Cathedral: Romanesque and Early English.’

in J.

Maddison (Ed.), XIII Medieval archaeology and architecture at Lichfield. The

British Archaeological Association. (1993), 17–35.

[14]

W. H. Pyne, The History of the Royal Residences, (London: 1819), 1, 35

and A. B. Clifton, ‘The cathedral church of Lichfield a description of its

fabric and a brief history of the episcopal see.’ (London: 1900), Bell Series, 68.

Also VCH, Staffordshire, 3, 149.

[15]

Willis (1861), 18.

[16]

The later roof is said to have been instigated by Bishop Walter Langton. See J.

Britton, The history and antiquities of the

See and cathedral church of Lichfield. (London: 1820), 28. It could have also been undertaken in the 1350s, see

note 5.

[17]

The position of the south round window between the lower stone vaulted roof and

the upper external roof, so that it cannot be seen from inside the cathedral,

has been said to be proof for the stone roof added later. See, J. C. Woodhouse,

A short account of Lichfield Cathedral. Lichfield: (Lichfield: 1811), 5.

.JPG)